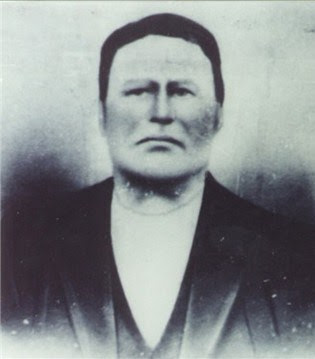

Samuel Paris McKinney (1822-1898)

The following story is about my wife Shirley's great-great-great grandfather. This story has been handed down for several generations, and was shared with me. Now I am sharing it with you.

Samuel Paris McKinney was born in 1822, and he lived most of his life in the rugged, wild mountains of Wyoming County, West Virginia. He received a land grant on Barker's Ridge where he made his home, but more often than not, could be found near his favorite hunting spot on Bee Tree Creek (which borders present day Wyoming and Raleigh counties). In Samuel Paris' days, there weren't many people in the Bee Tree Creek area and the hunting was excellent, perhaps even the best in the region. It was also considered so wild of an area that many men avoided it. People told tales of ferocious animals, evil spirits and even wild Indian hold-outs when speaking of the area. The tales grew even more frightening when they spoke of the great laurel thicket, a defining feature of the area. Samuel Paris liked it when he heard these stories; to him as long as people were afraid of the area it would remain wild and free of settlement. Taking advantage of the situation, he was often alone when he hunted, trapped and spent a great deal of time along Bee Tree Creek even though his official home was on Barker's Ridge, several miles away.

When Samuel Paris hunted, he carried with him a pack bag typical of men of the time. By his side was a mountain rifle and a tomahawk. His rifle was so long that many men found it nearly impossible to hold because the barrel was so long. There were newer rifles available to him, but his daddy had given him his rifle and it was a good rifle so he saw no need to "upgrade". He was known to be quite fearless in his exploits, taking chances that many deemed unnecessary but to him they were just everyday actions of living. Samuel Paris was known throughout the region as one of the first to raise hunting dogs, and his dogs were considered to be among the best bred and most well-trained in the region. Men would come from miles around to trade or buy a pup off of him, and it soon came to pass that having a good hunting dog by your side was essential to every hunting man in the area.

One time over on Bee Tree Creek, Samuel Paris had his favorite dog with him, and it wasn't too long until the dog picked up the trail of a great bear. When the bear realized it was being trailed, it broke into a full run right into the great laurel thicket. He had trained his dogs never to go into a laurel thicket after a bear because more often than not that action was a death sentence on the dog and quite often the man, too. But this time and against all its training, his favorite dog found a low trail and went into the laurel thicket after the bear.

Since this was his favorite dog, Samuel Paris saw no other option besides to go in after the dog. If it hadn't been his favorite dog, he probably would have just made camp and hoped the dog returned out of the thicket, but he just couldn't wait and hope when it came to his favorite dog. So against his better judgement he entered the laurel thicket after the dog. He planned on just retrieving the dog and getting out as quickly as possible, and his decision was justified after he entered the thicket. The laurel grew so thick that he was forced to crawl in many places, and seldom was there an area where a man could even stand upright. He was about a hundred yards into the laurel thicket when he located the dog, but soon realized that simply retrieving it wasn't an option. You see, the great bear had the dog penned up in a corner between two vertical cliffs on Bee Tree Creek, and was slowly closing in on it.

At this point, Samuel Paris was crawling along through the thicket as quickly as he could manage, trying to get to an open area where he could raise his gun. As it was, there was no chance of getting off a shot at the bear since he was practically dragging the rifle alongside of his body. He finally made his way into Bee Tree Creek, where the flowing water offered a slight opening in the laurel. But as he raised his rifle to shoot the bear, the bear had moved in so close to the trapped dog that it was impossible to get a shot at it for fear of hitting the dog.

Quick thinking coupled with the inherent and passionate bravery of a mountain Scotsman, Samuel Paris McKinney instantly came upon a plan. Without a moment's hesitation, he pulled out the tomahawk from his belt, ran up to the bear and grabbed the great beast by the hair on the nape of its neck, quickly and deftly swung the tomahawk once and split the bear's skull wide open, killing it instantly. For years afterward, stories were recounted about how Samuel Paris McKinney had killed a bear with only a tomahawk and in the process had saved his favorite hunting dog, all without getting so much as a single scratch on him.

In the years following this account, progress inevitably took its toll upon the region, and the great laurel thicket was cut down and the area along Bee Tree Creek was settled. Later, coal mines dotted the landscape. As the area grew in population, Samuel Paris began to stay on his land high up on Barker's Ridge, and in his last days raised and sold hunting dogs to make a living. Men would come from miles around to buy his dogs and hear him regale his tales of yesteryear. The time of the rugged mountaineer had come to an end and those times were now found only in story form. And oh what great stories Samuel Paris McKinney told.